In previous installments, Japanese beauty has been explored from various angles.

Concluding this special feature is an article by Masayuki Hirota, one of Japan’s leading watch journalists and editor-in-chief of the Japanese edition of luxury watch magazine Chronos.

How does the sense of beauty nurtured in Japan connect to Grand Seiko, and how is it kept alive? Divided into two parts, this installment will provide substantial insight.

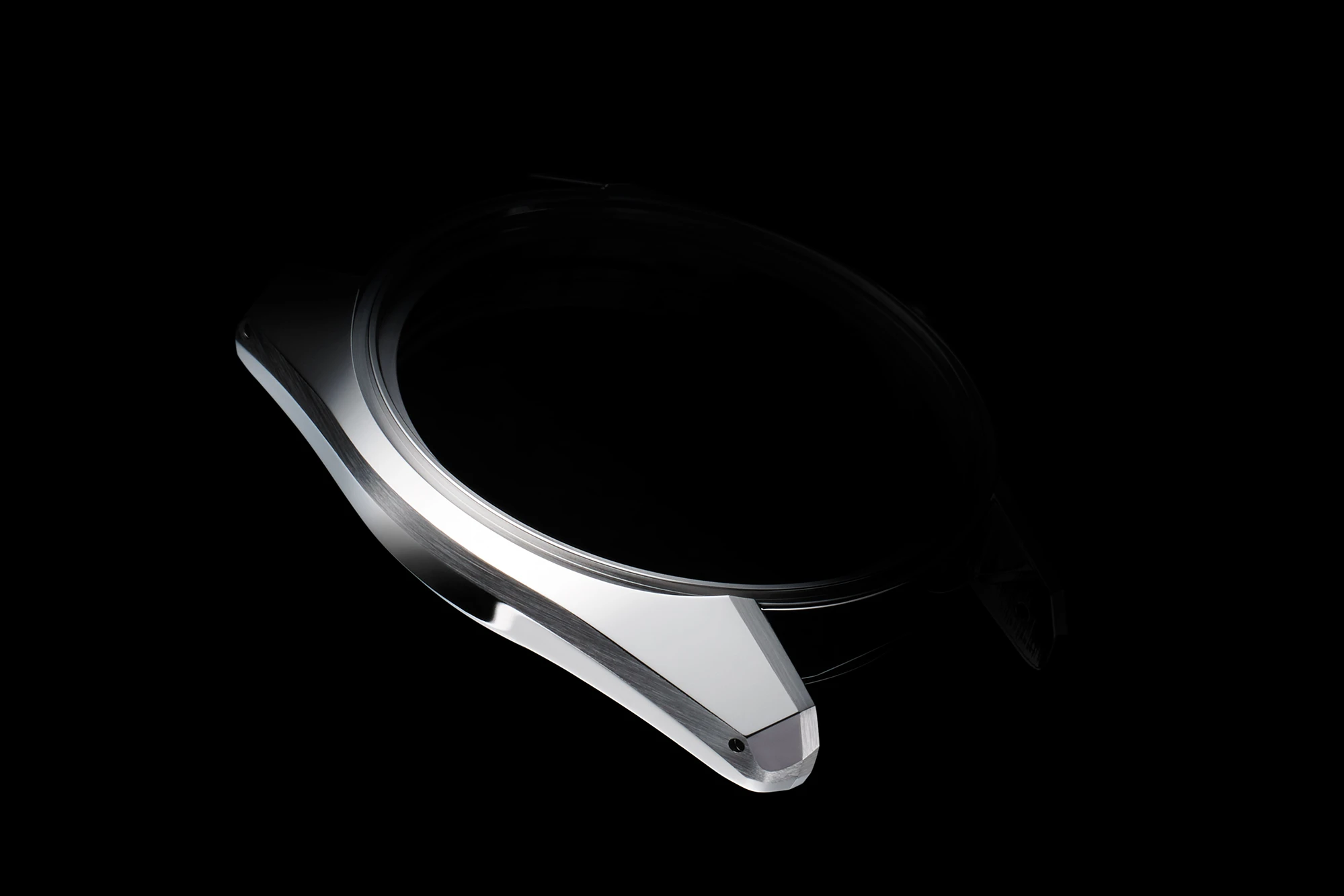

Today, Grand Seiko has many fans all over the world. The sentiment they uniformly share is the Japanese beauty found within every Grand Seiko. One reason is the distortion-free flat surfaces in Grand Seiko products.

The Japanese watch industry has primarily used cold forging techniques to process metal into cases and dials. In other words, metal molds are used to press metal with a force of several hundred tons to create the desired forms. The high precision and speed with which complex shapes can be produced make the method well suited for mass production. In addition, the forming process has the advantage of increasing the strength and durability of products.

However, cold forging also has its disadvantages. Because the metal is pressed in a mold, creating sharply defined corners and flat surfaces is challenging. Forging was once the prevailing method among Swiss watchmakers, but considering these disadvantages, some shifted to a case design without corners. Many other small-quantity watchmakers have moved to cutting—shaping the metal one by one—since the 1980s.

Left: The large, beautifully polished surface of the Grand Seiko case is reminiscent of a Japanese sword.

Right: The outstanding Zaratsu polishing technique creates flat, distortion-free surfaces.

In the case of Grand Seiko, however, the importance of high productivity and strength in their products compelled them to choose cold forging as the primary way forward. To overcome the demerits of forging, Grand Seiko began to use a technique called Zaratsu polishing extensively. The method involves preparing the surface of the case metal by pressing it against the front surface of a rotating aluminum disk covered with sandpaper. Requiring the reliable skills of a master craftsperson backed by many years of experience, it is a technique that has been lost among Swiss brands.

Grand Seiko has continued to increase both the size and number of surfaces with this extremely challenging finish. And ultimately, this has led the entire wristwatch to assume a beauty resembling that of a Japanese sword. Japanese swords are similarly forged and polished to perfection. In fact, many international watch journalists give high praise to Grand Seiko timepieces for their “uniquely Japanese forms, which hail from a culture of Japanese sword making.”

I believe that another aspect of Japanese beauty that can arguably be found in Grand Seiko watches is “light and shadow.”

Since its birth in 1960, Grand Seiko designers have strived to create timepieces with a “sparkle of beauty,” using Western luxury watches as a benchmark. Subsequently, the Grand Seiko Style was perfected with the 44GS model launched in 1967. From the case to the dial, hands, and indexes, the watch was polished to a flawless mirror finish, undoubtedly achieving a beautiful watch that “sparkles” no matter how you look at it.

However, while it may have been unconscious, the Japanese sense of light and shadow was already apparent in the design. Take the hands and indexes that make extensive use of flat surfaces, for example. The clever use of diagonal surfaces produced a combination of soft light and shadow that has been loved by the Japanese since ancient times and differs from the strong contrast of light and shadow found in the West. The surfaces of Grand Seiko’s hands and markers capture even the faintest rays of light that are so characteristically Japanese. Hence, the time can be read easily in any situation.

In recent years, Grand Seiko has amplified the expression of such light and shadow across the entire watch. The case effectively combines two types of polishing—Zaratsu polishing and hairline finishing—to create a more Japanese appearance by “subtracting” or softening the shades of light and shadow. As for the dial, in contrast to Swiss brands, which mainly use cutting processes to create geometric patterns, Grand Seiko achieves patterns of greater intricacy by employing a pressing technique. This has now become a great strength of the company.

The SBGA211, commonly known as the “snowflake dial,” which is unfailingly popular at home and abroad, and the SLGH005, affectionately known as the “white birch dial and won the Men’s Watch Prize at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève in November 2021, serve as good examples.

Another key point to consider when comparing with many Swiss watchmakers is the application of successive coats of lacquer to achieve a thick finish. This was initially intended to preserve the beauty of the dial, but it also produces a strong sense of depth in certain light conditions. Incidentally, the plating on the “snowflake dial” is actually silver. The use of silver to give the appearance of whiteness in reflected light is yet another elaborate means to create subtle variations in light and shadow.

This aesthetic of subtraction extends not only to the exterior but also to the heart of the watch. In 2020, Grand Seiko celebrated its 60th anniversary with the launch of two new movements, the mechanical high beat Caliber 9SA5 and the Spring Drive Caliber 9RA5, which achieve increased precision and a slimmer profile to deliver superior functionality. Launched the following year was Caliber 9RA2, in which the power reserve indicator was repositioned at the back of the movement.

Left: Mechanical high beat movement Caliber 9SA5.

Right: Spring Drive movement, Caliber 9RA2.

The finish of the 9SA5 movement is engraved with a stripe pattern inspired by the Shizukuishi River that runs through Iwate Prefecture, where the movement is made. By giving the surface a satin finish to reduce reflected light and create a soft feel, a striking contrast is made against the sharp brilliance of the diamond-cut ridgelines and edges of the bridge. The 9RA2, meanwhile, impresses with its soft glow resembling that of the hoarfrost found in the freezing temperatures of Shinshu in Nagano Prefecture, the birthplace of the Spring Drive. The edges of the respective parts have been carefully chamfered and subtly rounded. The technique commands such a high skill level that I honestly cannot fathom how it is done. Such delicate finishing accentuates the watch, creating a uniquely Japanese sense of light and shadow.

Instead of emphasizing Japanese elements, Grand Seiko timepieces have gradually come to embrace light and shadow through the brand’s pursuit of productivity, practicality, and technology, leading to the emergence of a uniquely Japanese sense of beauty. I sense an extremely Japanese sensibility in this evolutionary process, as well as in the very approach Grand Seiko adopts.

Masayuki Hirota

Born in 1974 in Osaka Prefecture. Watch journalist. Editor-in-Chief of the Japanese edition of Chronos, a luxury watch magazine. He actively writes for various magazines and web magazines in Japan and overseas. Co-author of A Japanese History of Time: How the Japanese Have Created ‘Time’ and Japan Made Tourbillon (Nikkan Kogyo Shimbun), among other publications.

text = Akiko Inamo

photography = Yu Mitamura